This past summer (2016) I designed the online section for The Cooper Union’s Summer Writing Program. Students in this program are mostly juniors and seniors in high schools from across the US, both private and public, although sometimes the program admits a high school sophomore or freshman college student. The program exposes students to college level reading and writing, and aims to open up the connection between reading, writing, and thinking so students become more confident readers of challenging texts and learn to approach writing as a process of exploration, investigation, and revision. We spend a lot of time taking students through all the stages of writing, from close reading and asking questions about a text to drafting and revising.

The Summer Writing Program takes three weeks, and the F2F classes meet Mondays through Thursdays for four hours each day. The online component also has to “meet” daily, but for two hours. I chose to use Google Hangouts for this synchronous component of the course, mostly because it was free, easy to use for students, and did not require any software installation, only a Google account. Only one student experienced problems with the connection, mostly because the summer house on a Maine island where she was staying did not have a strong wifi signal, but otherwise we did not have a lot of issues meeting online. When a connection was poor, a student would occasionally use sound only.

Google Docs and Courseblogs.org

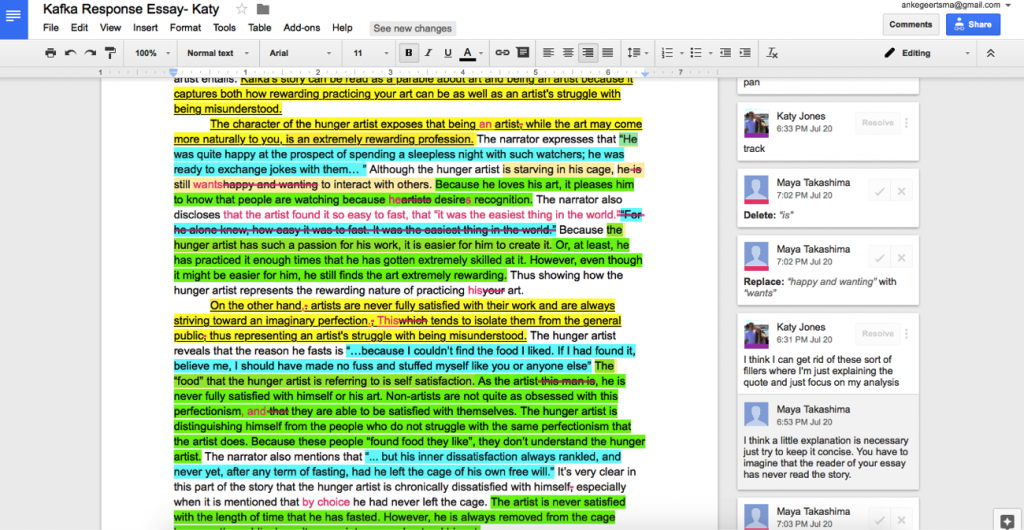

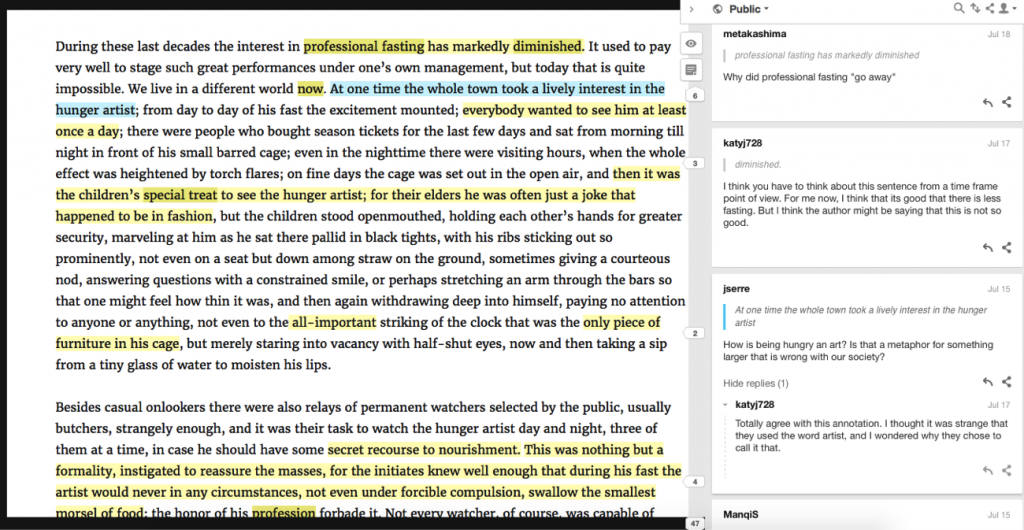

While connected through Hangouts, we worked in Google Docs and on the course site courseblogs.org. I created a shared folder in Google Docs for all written work. Often, we opened a document together to go over the content as a group, adding information or comments in the margins during the discussion. We also worked in one document together to generate questions after having read a text, for example. Within the shared folder, each student had their own personal folder for all their writing. Everyone had access to each other’s work so when doing peer review I could easily assign one or more students to go over someone else’s work. I asked students to never “resolve” each other’s comments in the margins, and, since we worked “in” each other’s documents so often and in various ways, writing really became synonymous with revision and process, as the image below shows:

Fig. 1, Kafka Response Essay with comments, Katy

So, although I hadn’t thought of it as such, and focused more annotation for reading, marginal comments in Google Docs became an essential part of the writing process in this course, and facilitated peer-review, close reading, and my own response to student work, as it allowed me to give focused, line-by-line feedback when needed. In the course evaluations, several students mentioned the ease of working with Google Docs and getting fast and a lot feedback on their work: “What was really effective was using Google Docs to be able to share documents and comment on each other’s papers so that there was a lot of feedback going around.”

The annotation tools I have been working on for the Interactive Technology and Pedagogy Certificate Program focus not so much on annotation as a part of the writing process but on annotation of “closed” or “static” texts such as literature and other published materials (though annotation makes them less “static”), which is what I intended to facilitate through the Hypothes.is plug-in on courseblogs.org. So, while we would read, annotate, and publish later drafts of student writing on the course site, Google Docs served as our drawing board where we went in between reading literature and posting student work on the site.

I created several pages on courseblogs.org. Since the course was a summer program and we did not have a traditional syllabus, I wrote a welcome and brief description of the course on the “welcome” page (set as static homepage). I created a separate page with detailed guidelines on how to use Google Docs, post on WordPress, and sign up for Hypothes.is. On a third page I posted all readings and videos and made the fourth page our blog. I set up Buddypress so all students could create an account and access the dashboard to post on the blog, and I enabled the Hypothes.is plugin on the “readings” page only.

The most time-consuming part of course preparation was converting some of the readings from PDF or other formats into text. I used Adobe PDF Converter but often the texts came out incomplete or inconsistent in layout, font and size. It would have been possible to annotate PDFs but I wanted to create an aesthetically pleasing site that would contain all our readings (with PDFs we would have had to leave the site to annotate). The time that goes into file conversion as well as copyright issues (I had to make sure all my text were copyright free or password protect the page), are definitely some of the downsides of reading and annotating online.

Using Annotation and Hypothes.is

Since the emphasis in the course lay on how to read complex texts, generate questions, and then write about the texts, we practiced with various close reading strategies so students could find out what worked best for them. Annotation was one of the four close reading strategies, and this is where students in the online class had a different experience from those in the F2F classes. To compare their experiences, and for students to reflect on their preferred strategies, we asked everyone to write short reflections.

This was the prompt for the reflection:

Now that we have used different strategies for close reading (i.e. annotation, dialogic journal, table, sentence imitation), reflect on their effectiveness and if and when you would use these strategies. Which strategy are you most likely to use? Which one do you really dislike? What made you think about the text in ways you would not have thought? Which one felt laborious or useless? Are there close reading strategies that work for one type of text but not for another? You don’t have to address all these questions in your response–the point is to reflect on your use of these strategies and think about what works best for you. Please write a 3-4 paragraph reflection.

With the students in the online class annotation had become part of the reading process. We did various exercises throughout the class: from “free” annotation (where I asked students just to write down any thoughts or questions that came to mind) to guided annotation (where I added questions in the margins that they had to address) to more focused annotation (where I asked them to focus only on words they did not know, for example). For them, annotation already became a habit: they annotated every text they read and commented on each other’s annotations.

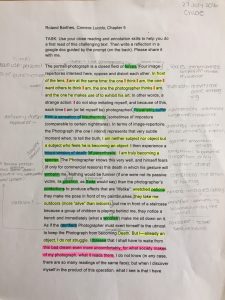

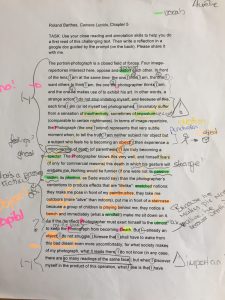

With the students in the F2F class, while some would annotate by themselves, instructors only did one specific in-class annotation exercise: like the online students, they annotated a part of Barthes’ Camera Lucida. Below are two students’ annotations:

Fig. 2, Annotations from F2F class, Chloe and Amélie

The students in the online class annotated the same text, but with guiding questions in the margins:

Fig. 3, Students responding to instructor’s questions in margins

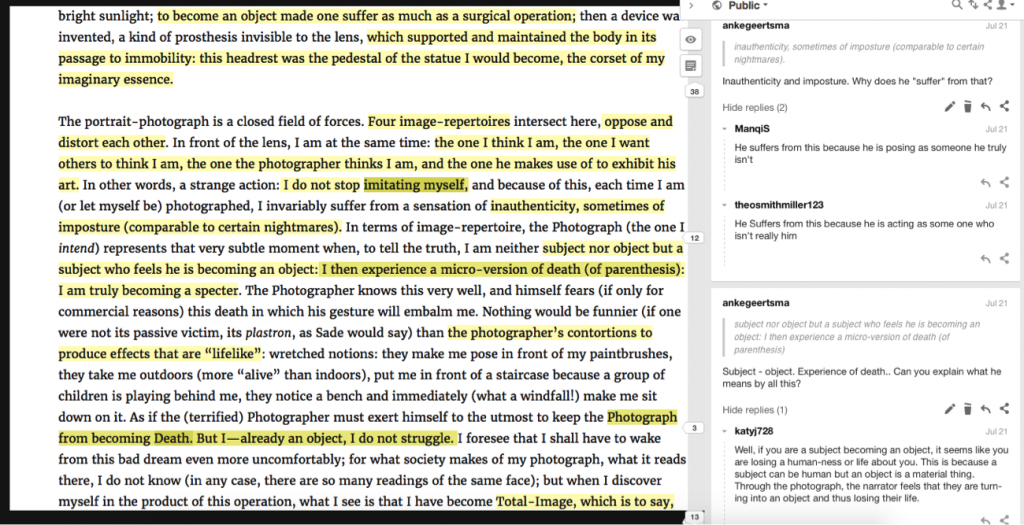

Students in the online class got in the habit of asking questions in the margins and responding to each other’s comments, as the image below shows:

Fig. 4, Students asking questions and responding to each other’s comments

Since close readings strategies were such an important part of the Summer Writing Program, we asked students to practice with various forms of close reading, such as a dialogic journals and even drawings and sentence imitation. In both the F2F and online classes, students and instructor also discussed how to annotate. In the close reading reflection, one student from the F2F class notes that this made a difference:

The strategy that helped me think about the text in ways I would have never thought of was annotation. Even though I have always used annotation, we have learned about new things to look for when annotating like for patterns and strangeness in the text and how to comprehend it (i.e. OED).

So, while most students were familiar with annotation and had done it in their high school classes, they benefited from more practice and discussion on annotation strategies and what makes for a “good” annotation. One of the students in the online class remarks that one of the few downsides of annotation was that sometimes, the annotations “were just personal feelings about the text.” This indicates that it is important to discuss with students what the purpose of annotation is, and, especially for those working online, what kind of annotations are most useful for their peers. Unlike individual in-class annotation exercises, these online tools require awareness of audience, which is something to address and come back to in class.

Overall, the students in the F2F and online classes say annotation is one of their preferred strategies for close reading, mostly because other forms can be time-consuming or do not add to their understanding of the text (sentence imitation and drawing mostly). Many students also point out that the preferred strategy depends on the kind of text they are reading. Poems and very complex works are generally considered as better candidates for more thorough strategies such as dialogic journals. Annotation is often the first step for many of these students, even if later on they decide to further tease out meaning using a different close reading strategy. One student notes that circling and drawing on the page is very helpful, which cannot so easily be done in an online space: “Circling words and connecting them to each other makes me see different patterns, without doing that I won’t see them.” This might be one of the downsides of online tools, since there is less flexibility in how to annotate–with annotations mostly limited to pop-up or marginal comments. In none of the online tools is it impossible to make different types of marks (such as lines, arrows, circles).

The students in the online class were asked some specific questions about taking the class online and using courseblogs.org and Hypothes.is. Below are the questions they were asked at the end of the course:

- What was effective about taking the SWP online?

- What were the challenges or difficulties taking the SWP online?

- Would you recommend the SWP online course to other students? Please explain why.

- What improvements to the online teaching structure would you recommend for the program’s future?

In response to these questions, and as mentioned earlier, the majority of students say that one of the pluses of taking the course online was the frequency and turnaround time for feedback and peer review, and the ability to literally be on the page together through Google Docs. As for the challenges of taking the course online, some mention that there were a few technical glitches while another student says that “taking it online actually made it easier.” Also, in response to the question whether they would recommend the course, they all say they would, mostly because of the feedback, the convenience, and the experience of “meeting” people from different places. One student notes, though, that being on the computer for two hours straight (during the synchronous part) could be tiring sometimes.

Another part of the evaluation shows that students are overall quite positive about Hypothes.is and do not feel like it was hard to set up an account or use the tool. They say that simply refreshing the page often solved the problem. Interestingly, the social aspect of Hypothes.is is ranked as the most positive by all students, and in their responses to the questions below the table, they all also comment that they learned from seeing each other’s comments, mostly because it allowed them to “see [a] different perspective,” “helped process [my] own thoughts,” or “helped clarify parts that were confusing.”

When describing how they read and annotated the readings, most students say that they read first by themselves and then went over the text again to read their peers’ annotations. Some annotated the first time they read the texts while others only did that on a second reading while also checking peer annotations. One student remarks that “[w]hen I got stuck, I would read the other comments for inspiration,” which shows how reading others’ comments can help students further their thinking.

Even though there were only a few students in this program, the evaluations suggest that the social aspect of the online tools was especially effective, for the students, and for myself, as it gave me a lot of insight into how they were processing the readings. Annotation through Hypothes.is was effective in my view, and a good solution for an online class like this one. I especially like that it is a plugin that easily integrates with your own site design, so it does not take over your theme (like Commentpress) or requires the use of a CMS (like Drupal) or hosted environment (like Annotation Studio and Classroom Salon).

Other aspects of the course structure that were effective in my view were the combination of the course site with Google Docs, even though I felt that we did not use the full potential of the blog because we drafted so much in Google Docs instead of on the blog page. Now, the blog page on courseblogs.org was merely the publication page for finished writing. I feel like I missed some of the potential here since students did not comment on each other’s work on the public-facing course site.

Another potential problem that I see is how to assess student annotation and how to bridge the online and offline discussion in a hybrid class. Even now, in the online class, it was difficult to bring all the compelling comments made in the margins to class discussion (in our Google Hangouts meeting). Students did not fully remember all their comments and sometimes it felt like their discussion in the margins had been “resolved” so when you asked them to address it, they merely summarized what was said there. In a hybrid course, it is probably important to find strategies to create a bridge between the online reading discussion and the in-class one, maybe by asking students to copy or bring in questions/comments or by pulling up the online text in class.

Other issues to be cognizant of going into my next course with Hypothes.is and a course site is that students might be more hesitant to share annotations online than they would if they were to annotate by themselves, and that I am giving them a pre-set space for annotation, which does not allow for more creative annotation (such as drawing, circling, etc). Also, it is important to discuss and guide students in how to annotate (including what a “productive utterance” is for themselves and their peers), and to address the privacy issues that play a role when writing in a public space like a course site. I am leaning toward including some annotations in-class and on paper to let students experience the difference between analogue individual versus online social annotation, and to base a discussion on this.